For the past few years The Improvement Service have been attempting to enable greater access to better data from local government so that is can be used for far wider purposes than it was initially collected for. This has proven to be a very tricky and resource-intensive endeavour. Therefore, over the course of this summer, when we embarked on a report for Scottish Government about planning data specifically, we’ve been taking a step back to try and understand why such data can be so problematic.

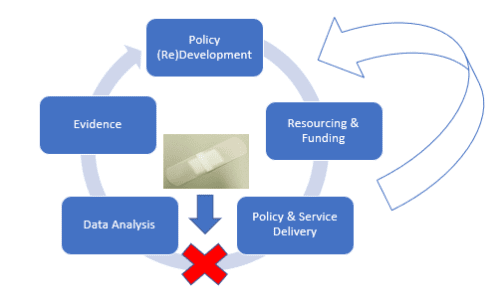

In an ideal, nay utopian, world our data should facilitate our evidence-building, which is then used to make decisions and formulate policy about how to improve our lives and the world around us. However, over the years, policy development and any associated data requirement have become increasing disconnected. Occasionally, there might be a sentence or two in legislative documents about providing a notification or specific information back to a responsible body. We also see examples of legislation proposing that resources (like maps) be created about policies that are made available for the public to access. There are perhaps good reasons why policy and legislation have been written in this rather generic, woolly way in years gone by – our various policy and service delivery bodies have been given a certain amount of autonomy to go about their business in the best way they see fit – so long as they deliver what’s being asked of them.

However, times are changing and changing fast. Delivery bodies are no longer expected to operate in silos. Holistic and collaborative solutions to problem-solving are generally accepted to be the most sensible and appropriate way forward. Digital and data technology advances have changed everything and, perhaps influenced by our personal lives, there’s an expectation that we should be able to get quick answers and intelligence about anything we wish.

Delivery bodies rightly focus their efforts on doing what they are specifically resourced and funded to do. When new policy and legislation is created that necessitates a change of focus, it is generally classed as a ‘new burden’ and should be resourced accordingly. In times of fiscal restraint, this is also a potential reason for policy not focusing on any great detail about data requirements.

Without an embedded requirement for good, standardised data within policy and legislation, it is almost impossible to then collect and analyse data to provide evidence to show whether a policy is actually achieving what it set out to achieve in the first place (and hence whether it needs tweaking or changing completely). It means policy makers can become unaccountable.

Because of these reasons, we are seeing a proliferation of ‘sticking plasters of data’ initiatives wherever we look. Currently, until policy makers pay more attention to the importance of data, we are always left playing catch up with data – trying to engineer what has been created (often for very constrained and specific reasons) to make it more intelligible, understandable and analysable. In that way, we at least have a chance of using facts and evidence to influence things for the better.

As always, these problems are not uniform and we do see pockets of success and excellence. The national address data is captured by each responsible body to a recognised standard – largely because there’s a statutory requirement and an inherent importance in doing this well – but also because funding was supplied to build a robust framework around it. Consequently, the data is used ubiquitously across the country for all sorts of purposes and has also been commercialised. Similarly, Vacant and Derelict Land data has become a mandatory, yearly statistical return which is accompanied by £10million of funding that can be used to bring land back into use. Both the mandating and inherent benefit in providing good data has improved its quality. What we’re seeing here is that data is only ever as good as the importance that is placed upon it.

Where we do not have those legislative or funding levers, we’re having to find alternative approaches. An example of this sticking plaster approach to data is the Spatial Hub. Using the blueprint of the address data success, we built an online platform to collect whatever data was currently being created (local government being our main focus), then attempted to build nationally consistent, aggregated datasets to make available in standardised ways (i.e. with structured metadata and APIs) to the entire data community. Ideally, like the address data, we would like each data provider to start adopting set standards to make this whole process far more efficient. But, that is particularly difficult to effect if the provider doesn’t recognise any specific benefit to themselves and are already struggling for resources. So, longer term, that is the biggest problem we must overcome using both a carrot and stick approach – making data improvements palatable, pragmatic but also essential.

In the coming years, we will be working alongside colleagues in local and central government to try and agree/implement standards as part of a wider collaborative work piece looking at nationwide data across planning, community & land, health and social care, roads and transport, environment and pollution, utilities – basically whatever area needs it. We’ll also be conducting a series of activity that looks to promote these concepts, essentially trying to educate and inform those non-data specialists, to effect cultural change on the importance of data in everything we do.